|

26.6.2013 |

EN |

Official Journal of the European Union |

L 174/1 |

REGULATION (EU) No 549/2013 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL

of 21 May 2013

on the European system of national and regional accounts in the European Union

(Text with EEA relevance)

THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION,

Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, and in particular Article 338(1) thereof,

Having regard to the proposal from the European Commission,

After transmission of the draft legislative act to the national parliaments,

Having regard to the opinion of the European Central Bank (1),

Acting in accordance with the ordinary legislative procedure (2),

Whereas:

|

(1) |

Policymaking in the Union and monitoring of the economies of the Member States and of the economic and monetary union (EMU) require comparable, up-to-date and reliable information on the structure of the economy and the development of the economic situation of each Member State or region. |

|

(2) |

The Commission should play a part in the monitoring of the economies of the Member States and of the EMU and, in particular, report regularly to the Council on the progress made by Member States in fulfilling their obligations relating to the EMU. |

|

(3) |

Citizens of the Union need economic accounts as a basic tool for analysing the economic situation of a Member State or region. For the sake of comparability, such accounts should be drawn up on the basis of a single set of principles that are not open to differing interpretations. The information provided should be as precise, complete and timely as possible in order to ensure maximum transparency for all sectors. |

|

(4) |

The Commission should use aggregates of national and regional accounts for Union administrative purposes and, in particular, budgetary calculations. |

|

(5) |

In 1970 an administrative document entitled ‘European System of Integrated Economic Accounts(ESA)’ was published, covering the field governed by this Regulation. That document was drawn up solely by the Statistical Office of the European Communities on its responsibility alone and was the outcome of several years’ work, by that office together with Member States’ national statistical institutes, aimed at devising a system of national accounts to meet the requirements of the European Communities’ economic and social policy. It constituted the Community version of the United Nations System of National Accounts which had been used by the Communities up to that time. In order to update the original text a second edition of the document was published in 1979 (3). |

|

(6) |

Council Regulation (EC) No 2223/96 of 25 June 1996 on the European system of national and regional accounts in the Community (4) set up a system of national accounts to meet the requirements of the economic, social and regional policy of the Community. That system was broadly consistent with the then new System of National Accounts, which was adopted by the United Nations Statistical Commission in February 1993 (1993 SNA), so that the results in all member countries of the United Nations would be internationally comparable. |

|

(7) |

The 1993 SNA was updated in the form of a new System of National Accounts (2008 SNA) adopted by the United Nations Statistical Commission in February 2009 in order to bring national accounts more into line with the new economic environment, advances in methodological research, and the needs of users. |

|

(8) |

There is a need to revise the European System of Accounts set up by Regulation (EC) No 2223/96 (the ESA 95) in order to take into account the developments in the SNA so that the revised European System of Accounts, as established by this Regulation, constitutes a version of the 2008 SNA that is adapted to the structures of the Member States’ economies, and so that the data of the Union are comparable with those compiled by its main international partners. |

|

(9) |

For the purpose of setting up environmental economic accounts as satellite accounts to the revised European System of Accounts, Regulation (EU) No 691/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 July 2011 on European environmental economic accounts (5) established a common framework for the collection, compilation, transmission and evaluation of European environmental economic accounts. |

|

(10) |

In the case of environmental and social accounts, the Communication from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament of 20 August 2009, entitled ‘GDP and beyond — Measuring progress in a changing world’, should also be fully taken into account. There is a need to vigorously pursue methodological studies and data tests in particular on issues related to ‘GDP and beyond’ and the Europe 2020 strategy with the aim of developing a more comprehensive measurement approach for wellbeing and progress in order to support the promotion of smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. In this context, the issues of environmental externalities and social inequalities should be addressed. The issue of productivity changes should also be taken into account. This should allow data that complement GDP aggregates to be made available as soon as possible. The Commission should present in 2013, to the European Parliament and to the Council, a follow-up Communication on ‘GDP and beyond’ and, if appropriate, legislative proposals in 2014. Data on national and regional accounts should be seen as one means of pursuing those aims. |

|

(11) |

The possible use of new, automated and real-time collection methods should be explored. |

|

(12) |

The revised European System of Accounts set up by this Regulation (ESA 2010) includes a methodology, and a transmission programme which defines the accounts and tables that are to be provided by all Member States according to specified deadlines. The Commission should make those accounts and tables available to users on specific dates and, where relevant, according to a pre-announced release calendar, particularly with regard to monitoring economic convergence and achieving close coordination of the Member States’ economic policies. |

|

(13) |

A user-oriented approach to publishing data should be adopted, thus providing accessible and useful information to Union citizens and other stakeholders. |

|

(14) |

The ESA 2010 is gradually to replace all other systems as a reference framework of common standards, definitions, classifications and accounting rules for drawing up the accounts of the Member States for the purposes of the Union, so that results that are comparable between the Member States can be obtained. |

|

(15) |

In accordance with Regulation (EC) No 1059/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 May 2003 on the establishment of a common classification of territorial units for statistics (NUTS) (6), all Member States’ statistics that are transmitted to the Commission and that are to be broken down by territorial units should use the NUTS classification. Consequently, in order to establish comparable regional statistics, the territorial units should be defined in accordance with the NUTS classification. |

|

(16) |

The transmission of data by the Member States, including the transmission of confidential data, is governed by the rules set out in Regulation (EC) No 223/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 March 2009 on European statistics (7). Accordingly, measures that are taken in accordance with this Regulation should, therefore, also ensure the protection of confidential data and that no unlawful disclosure or non-statistical use occurs when European statistics are produced and disseminated. |

|

(17) |

A task force has been set up to further examine the issue of the treatment of financial intermediation services indirectly measured (FISIM) in national accounts, including the examination of a risk-adjusted method that excludes risk from FISIM calculations in order to reflect the expected future cost of realised risk. Taking into consideration the findings of the task force, it may be necessary to amend the methodology for the calculation and allocation of FISIM, by means of a delegated act, in order to provide improved results. |

|

(18) |

Research and development expenditure constitutes investment and should therefore be recorded as gross fixed capital formation. However, it is necessary to specify, by means of a delegated act, the format of the research and development expenditure data to be recorded as gross fixed capital formation when a sufficient level of confidence in the reliability and comparability of the data is reached through a test exercise based on the development of supplementary tables. |

|

(19) |

Council Directive 2011/85/EU of 8 November 2011 on requirements for budgetary frameworks of the Member States (8) requires publication of relevant information on contingent liabilities with potentially large impacts on public budgets, including government guarantees, non-performing loans, and liabilities stemming from the operation of public corporations including the extent thereof. Those requirements necessitate additional publication to that required under this Regulation. |

|

(20) |

In June 2012, the Commission (Eurostat) established a Task Force on the implications of Directive 2011/85/EU for the collection and dissemination of fiscal data, which focused on the implementation of the requirements related to contingent liabilities and other relevant information which may indicate potentially large impacts on public budgets, including government guarantees, liabilities of public corporations, Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs), non-performing loans, and government participation in the capital of corporations. Fully implementing the work of that Task Force would contribute to the proper analysis of the underlying economic relationships of PPP contracts, including construction, availability and demand risks, as appropriate, and capture of implicit debts of off balance sheet PPPs, thereby fostering increased transparency and reliable debt statistics. |

|

(21) |

The Economic Policy Committee set up by Council Decision 74/122/EEC (9) (EPC) has been carrying out work in relation to the sustainability of pensions and pension reforms. The work of statisticians on the one hand and of experts on ageing populations working under the auspices of the EPC on the other hand should be closely coordinated, at both national and European levels, with respect to macroeconomic assumptions and other actuarial parameters in order to ensure consistency and cross-country comparability of the results as well as efficient communication to users and stakeholders of the data and information related to pensions. It should also be made clear that accrued-to-date pension entitlements in social insurance are not as such a measure of the sustainability of public finances. |

|

(22) |

Data and information on Member States’ contingent liabilities are provided in the context of the work related to the multilateral surveillance procedure in the Stability and Growth Pact. By July 2018, the Commission should issue a report evaluating whether those data should be made available in the context of the ESA 2010. |

|

(23) |

It is important to underline the significance of Member States’ regional accounts for the regional, economic and social cohesion policies of the Union as well as the analysis of economic interdependencies. Moreover, the need to increase the transparency of accounts at a regional level, including government accounts, is recognised. The Commission (Eurostat) should pay particular attention to the fiscal data of regions where Member States have autonomous regions or governments. |

|

(24) |

In order to amend Annex A of this Regulation with a view to ensuring its harmonised interpretation or international comparability, the power to adopt acts in accordance with Article 290 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) should be delegated to the Commission. It is of particular importance that the Commission carry out appropriate consultations during its preparatory work, including with the European Statistical System Committee established under Regulation (EC) No 223/2009. Moreover, pursuant to Articles 127(4) and 282(5) TFEU, it is of importance that the Commission carry out during its preparatory work, where relevant, consultations with the European Central Bank in its fields of competence. The Commission, when preparing and drawing up delegated acts, should ensure a simultaneous, timely and appropriate transmission of relevant documents to the European Parliament and to the Council. |

|

(25) |

Most statistical aggregates used in the economic governance framework of the Union, in particular the excessive deficit and the macroeconomic imbalances procedures, are defined by reference to the ESA. When providing data and reports under those procedures, the Commission should give appropriate information about the impact on the relevant aggregates of the ESA 2010 methodological changes introduced by delegated acts in accordance with the provisions of this Regulation. |

|

(26) |

The Commission will carry out an evaluation as to whether the data on Research and Development have reached a sufficient level of quality both in current prices and in volume terms for national accounts purposes before the end of May 2013, in close cooperation with the Member States, with a view to ensuring the reliability and comparability of the ESA Research and Development data. |

|

(27) |

Since the implementation of this Regulation will require major adaptations in the national statistical systems, derogations will be granted by the Commission to Member States. In particular, the transmission programme of national accounts data should take into consideration the fundamental political and statistical changes that have occurred in some Member States during the reference periods of the programme. The derogations granted by the Commission should be temporary and subject to review. The Commission should provide support to the Member States concerned in their efforts to ensure the required adaptations to their statistical systems so that those derogations can be discontinued as soon as possible. |

|

(28) |

Reducing transmission deadlines could add significant pressure and costs for respondents and national statistical institutes in the Union, with the risk of a lower quality of data being produced. A balance of advantages and disadvantages should, therefore, be considered when setting the data transmission deadlines. |

|

(29) |

In order to ensure uniform conditions for the implementation of this Regulation, implementing powers should be conferred on the Commission. Those powers should be exercised in accordance with Regulation (EU) No 182/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 February 2011 laying down the rules and general principles concerning mechanisms for control by Member States of the Commission’s exercise of implementing powers (10). |

|

(30) |

Since the objective of this Regulation, namely the establishment of a revised European System of Accounts, cannot be sufficiently achieved by the Member States and can be better achieved at Union level, the Union may adopt measures, in accordance with the principle of subsidiarity as set out in Article 5 of the Treaty on European Union. In accordance with the principle of proportionality, as set out in that Article, this Regulation does not go beyond what is necessary in order to achieve that objective. |

|

(31) |

The European Statistical System Committee has been consulted. |

|

(32) |

The Committee on Monetary, Financial and Balance of Payments Statistics set up by Council Decision 2006/856/EC of 13 November 2006 establishing a Committee on monetary, financial and balance of payments statistics (11) and the Gross National Income Committee (GNI Committee) set up by Council Regulation (EC, Euratom) No 1287/2003 of 15 July 2003 on the harmonisation of gross national income at market prices (GNI Regulation) (12) have been consulted, |

HAVE ADOPTED THIS REGULATION:

Article 1

Subject matter

1. This Regulation sets up the European System of Accounts 2010 (‘the ESA 2010’ or ‘the ESA’).

2. The ESA 2010 provides for:

|

(a) |

a methodology (Annex A) on common standards, definitions, classifications and accounting rules that shall be used for compiling accounts and tables on comparable bases for the purposes of the Union, together with results as required under Article 3; |

|

(b) |

a programme (Annex B) setting out the time limits by which Member States shall transmit to the Commission (Eurostat) the accounts and tables to be compiled in accordance with the methodology referred to in point (a). |

3. Without prejudice to Articles 5 and 10, this Regulation shall apply to all Union acts that refer to the ESA or its definitions.

4. This Regulation does not oblige any Member State to use the ESA 2010 in compiling accounts for its own purposes.

Article 2

Methodology

1. The methodology of the ESA 2010 referred to in point (a) of Article 1(2) is set out in Annex A.

2. The Commission shall be empowered to adopt delegated acts in accordance with Article 7, concerning amendments to the ESA 2010 methodology in order to specify and improve its content for the purpose of ensuring a harmonised interpretation or to ensure international comparability provided that they do not change its underlying concepts, do not require additional resources for producers within the European Statistical System for their implementation, and do not cause a change in own resources.

3. In the event of doubt regarding the correct implementation of the ESA 2010 accounting rules, the Member State concerned shall request clarification from the Commission (Eurostat). The Commission (Eurostat) shall act promptly both in examining the request and in communicating its advice on the requested clarification to the Member State concerned and all other Member States.

4. Member States shall carry out the calculation and allocation of financial intermediation services indirectly measured (FISIM) in national accounts in accordance with the methodology described in Annex A. The Commission shall be empowered to adopt before 17 September 2013 delegated acts in accordance with Article 7 laying down a revised methodology for the calculation and allocation of FISIM. In exercising its power pursuant to this paragraph, the Commission shall ensure that such delegated acts do not impose a significant additional administrative burden on the Member States or on the respondent units.

5. Research and development expenditure shall be recorded, by Member States, as gross fixed capital formation. The Commission shall be empowered to adopt delegated acts in accordance with Article 7 to ensure the reliability and comparability of the ESA 2010 data of the Member States on research and development. In exercising its power pursuant to this paragraph, the Commission shall ensure that such delegated acts do not impose a significant additional administrative burden on the Member States or on the respondent units.

Article 3

Transmission of data to the Commission

1. The Member States shall transmit to the Commission (Eurostat) the accounts and tables set out in Annex B within the time limits specified therein for each table.

2. Member States shall transmit to the Commission the data and metadata required by this Regulation in accordance with a specified interchange standard and other practical arrangements.

The data shall be transmitted or uploaded by electronic means to the single entry point for data at the Commission. The interchange standard and other practical arrangements for the transmission of the data shall be defined by the Commission by means of implementing acts. Those implementing acts shall be adopted in accordance with the examination procedure referred to in Article 8(2).

Article 4

Quality assessment

1. For the purpose of this Regulation, the quality criteria set out in Article 12(1) of Regulation (EC) No 223/2009 shall apply to the data to be transmitted in accordance with Article 3 of this Regulation.

2. Member States shall provide the Commission (Eurostat) with a report on the quality of the data to be transmitted in accordance with Article 3.

3. In applying the quality criteria referred to in paragraph 1 to the data covered by this Regulation, the modalities, structure, periodicity and assessment indicators of the quality reports shall be defined by the Commission by means of implementing acts. Those implementing acts shall be adopted in accordance with the examination procedure referred to in Article 8(2).

4. The Commission (Eurostat) shall assess the quality of the data transmitted.

Article 5

Date of application and of first transmission of data

1. The ESA 2010 shall be applied for the first time to data established in accordance with Annex B to be transmitted from 1 September 2014.

2. The data shall be transmitted to the Commission (Eurostat) in accordance with the time limits laid down in Annex B.

3. In accordance with paragraph 1, until the first transmission of data based on the ESA 2010, Member States shall continue to send to the Commission (Eurostat) the accounts and tables established by applying the ESA 95.

4. Without prejudice to Article 19 of Council Regulation (EC, Euratom) No 1150/2000 of 22 May 2000 implementing Decision 2007/436/EC, Euratom on the system of the European Communities own resources (13), the Commission and the Member State concerned shall check that this Regulation is being applied correctly and shall submit the outcome of those checks to the Committee referred to in Article 8(1) of this Regulation.

Article 6

Derogations

1. In so far as a national statistical system necessitates major adaptations for the application of this Regulation, the Commission shall grant temporary derogations to Member States by means of implementing acts. Those derogations shall expire not later than 1 January 2020. Those implementing acts shall be adopted in accordance with the examination procedure referred to in Article 8(2).

2. The Commission shall grant a derogation pursuant to paragraph 1 only for a period sufficient to allow the Member State concerned to adapt its statistical system. The proportion of the Member State’s GDP within the Union or within the euro area shall not constitute in itself a justification for granting a derogation. Where appropriate, the Commission shall provide support to the Member States concerned in their efforts to ensure the required adaptations to their statistical system.

3. For the purposes set out in paragraphs 1 and 2, the Member State concerned shall present a duly justified request to the Commission not later than 17 October 2013.

The Commission, after consulting the European Statistical System Committee, shall report to the European Parliament and the Council not later than 1 July 2018 on the application of the granted derogations in order to verify whether they are still justified.

Article 7

Exercise of the delegation

1. The power to adopt delegated acts is conferred on the Commission subject to the conditions laid down in this Article.

2. The power to adopt delegated acts referred to in Article 2(2) and (5) shall be conferred on the Commission for a period of five years, from 16 July 2013. The power to adopt delegated acts referred to in Article 2(4) shall be conferred on the Commission for a period of two months from 16 July 2013. The Commission shall draw up a report in respect of the delegation of power not later than nine months before the end of the five-year period. The delegation of power shall be tacitly extended for periods of an identical duration, unless the European Parliament or the Council opposes such extension not later than three months before the end of each period.

3. The delegation of power referred to in Article 2(2), (4) and (5) may be revoked at any time by the European Parliament or by the Council.

A decision to revoke shall put an end to the delegation of power specified in that Decision. It shall take effect the day following the publication of the decision in the Official Journal of the European Union or at a later date specified therein. It shall not affect the validity of any delegated acts already in force.

4. As soon as it adopts a delegated act, the Commission shall notify it simultaneously to the European Parliament and to the Council.

5. A delegated act adopted pursuant to Article 2(2), (4) and (5) shall enter into force only if no objection has been expressed either by the European Parliament or the Council within a period of three months of notification of that act to the European Parliament and the Council or if, before the expiry of that period, the European Parliament and the Council have both informed the Commission that they will not object. That period shall be extended by three months at the initiative of the European Parliament or of the Council.

Article 8

Committee

1. The Commission shall be assisted by the European Statistical System Committee established by Regulation (EC) No 223/2009. That committee is a committee within the meaning of Regulation (EU) No 182/2011.

2. Where reference is made to this paragraph, Article 5 of Regulation (EU) No 182/2011 shall apply.

Article 9

Cooperation with other committees

1. On all matters falling within the competence of the Committee on Monetary, Financial and Balance of Payments Statistics established by Decision 2006/856/EC, the Commission shall request the opinion of that Committee in accordance with Article 2 of that Decision.

2. The Commission shall communicate to the Gross National Income Committee (‘GNI Committee’) established by Regulation (EC, Euratom) No 1287/2003 any information concerning the implementation of this Regulation which is necessary for the performance of the GNI Committee’s duties.

Article 10

Transitional provisions

1. For budgetary and own resources purposes, the European System of Accounts as referred to in Article 1(1) of Regulation (EC, Euratom) No 1287/2003 and the legal acts relating thereto, in particular Regulation (EC, Euratom) No 1150/2000 and Council Regulation (EEC, Euratom) No 1553/89 of 29 May 1989 on the definitive uniform arrangements for the collection of own resources accruing from value added tax (14), shall continue to be the ESA 95 while Council Decision 2007/436/EC, Euratom of 7 June 2007 on the system of the European Communities’ own resources (15) remains in force.

2. For the purpose of determination of the VAT-based own resource, and by way of exception to paragraph 1, the Member States may use data based on the ESA 2010 while Decision 2007/436/EC, Euratom remains in force, where the required detailed ESA 95 data are not available.

Article 11

Reporting on implicit liabilities

By 2014, the Commission shall submit a report to the European Parliament and to the Council containing existing information on PPPs and other implicit liabilities, including contingent liabilities, outside government.

By 2018, the Commission shall submit a further report to the European Parliament and to the Council assessing the extent to which the information on liabilities published by the Commission (Eurostat) represents the entirety of the implicit liabilities, including contingent liabilities, outside government.

Article 12

Review

By 1 July 2018 and every five years thereafter, the Commission shall submit a report on the application of this Regulation to the European Parliament and the Council.

The report shall evaluate, inter alia:

|

(a) |

the quality of data on national and regional accounts; |

|

(b) |

the effectiveness of this Regulation and the monitoring process applied to the ESA 2010; and |

|

(c) |

the progress on contingent liabilities data and on the availability of ESA 2010 data. |

Article 13

Entry into force

This Regulation shall enter into force on the twentieth day following that of its publication in the Official Journal of the European Union.

This Regulation shall be binding in its entirety and directly applicable in all Member States.

Done at Strasbourg, 21 May 2013.

For the European Parliament

The President

M. SCHULZ

For the Council

The President

L. CREIGHTON

(1) OJ C 203, 9.7.2011, p. 3.

(2) Position of the European Parliament of 13 March 2013 (not yet published in the Official Journal) and decision of the Council of 22 April 2013.

(3) Commission (Eurostat), European System of Integrated Economic Accounts (ESA), second edition, Statistical Office of the European Communities, Luxembourg, 1979.

(4) OJ L 310, 30.11.1996, p. 1.

(5) OJ L 192, 22.7.2011, p. 1.

(6) OJ L 154, 21.6.2003, p. 1.

(7) OJ L 87, 31.3.2009, p. 164.

(8) OJ L 306, 23.11.2011, p. 41.

(9) Council Decision 74/122/EEC of 18 February 1974 setting up an Economic Policy Committee (OJ L 63, 5.3.1974, p. 21).

(10) OJ L 55, 28.2.2011, p. 13.

(11) OJ L 332, 30.11.2006, p. 21.

(12) OJ L 181, 19.7.2003, p. 1.

(13) OJ L 130, 31.5.2000, p. 1.

(14) OJ L 155, 7.6.1989, p. 9.

(15) OJ L 163, 23.6.2007, p. 17.

ANNEX A

|

CHAPTER 1 |

GENERAL FEATURES AND BASIC PRINCIPLES |

GENERAL FEATURES

Globalisation

USES OF THE ESA 2010

Framework for analysis and policy

Characteristics of the ESA 2010 concepts

Classification by sector

Satellite accounts

The ESA 2010 and the 2008 SNA

The ESA 2010 and the ESA 95

BASIC PRINCIPLES OF THE ESA 2010 AS A SYSTEM

Statistical units and their groupings

Institutional units and sectors

Local KAUs and industries

Resident and non-resident units; total economy and rest of the world

Flows and stocks

Flows

Transactions

Properties of transactions

Interactions versus intra-unit transactions

Monetary versus non-monetary transactions

Transactions with and without counterparts

Rearranged transactions

Rerouting

Partitioning

Recognising the principal party to a transaction

Borderline cases

Other changes in assets

Other changes in the volume of assets and liabilities

Holding gains and losses

Stocks

The system of accounts and the aggregates

Rules of accounting

Terminology for the two sides of the accounts

Double entry/quadruple entry

Valuation

Special valuations concerning products

Valuation at constant prices

Time of recording

Consolidation and netting

Consolidation

Netting

Accounts, balancing items and aggregates

The sequence of accounts

The goods and services account

The rest of the world account

Balancing items

Aggregates

GDP: a key aggregate

The input-output framework

Supply and use tables

Symmetric input-output tables

|

CHAPTER 2 |

UNITS AND GROUPINGS OF UNITS |

THE LIMITS OF THE NATIONAL ECONOMY

THE INSTITUTIONAL UNITS

Head offices and holding companies

Groups of corporations

Special purpose entities

Captive financial institutions

Artificial subsidiaries

Special purpose units of general government

THE INSTITUTIONAL SECTORS

Non-financial corporations (S.11)

Public non-financial corporations (S.11001)

National private non-financial corporations (S.11002)

Foreign controlled non-financial corporations (S.11003)

Financial corporations (S.12)

Financial intermediaries

Financial auxiliaries

Financial corporations other than financial intermediaries and financial auxiliaries

Institutional units included in the financial corporations sector

Subsectors of financial corporations

Combining subsectors of financial corporations

Subdividing subsectors of financial corporations into public, national private and foreign controlled financial corporations

Central bank (S.121)

Deposit-taking corporations except the central bank (S.122)

MMF (S.123)

Non-MMF investment funds (S.124)

Other financial intermediaries, except insurance corporations and pension funds (S.125)

Financial vehicle corporations engaged in securitisation transactions (FVC)

Security and derivative dealers, financial corporations engaged in lending and specialised financial corporations

Financial auxiliaries (S.126)

Captive financial institutions and money lenders (S.127)

Insurance corporations (S.128)

Pension funds (S.129)

General government (S.13)

Central government (excluding social security funds) (S.1311)

State government (excluding social security funds) (S.1312)

Local government (excluding social security funds) (S.1313)

Social security funds (S.1314)

Households (S.14)

Employers and own-account workers (S.141 and S.142)

Employees (S.143)

Recipients of property income (S.1441)

Recipients of pensions (S.1442)

Recipients of other transfers (S.1443)

Non-profit institutions serving households (S.15)

Rest of the world (S.2)

Sector classification of producer units for main standard legal forms of ownership

LOCAL KIND-OF-ACTIVITY UNITS AND INDUSTRIES

The local kind-of-activity unit

Industries

Classification of industries

UNITS OF HOMOGENEOUS PRODUCTION AND HOMOGENEOUS BRANCHES

The unit of homogeneous production

The homogeneous branch

|

CHAPTER 3 |

TRANSACTIONS IN PRODUCTS AND NON-PRODUCED ASSETS |

TRANSACTIONS IN PRODUCTS IN GENERAL

PRODUCTION AND OUTPUT

Principal, secondary and ancillary activities

Output (P.1)

Institutional units: distinction between market, for own final use and non-market

Time of recording and valuation of output

Products of agriculture, forestry and fishing (Section A)

Manufactured products (Section C); construction work (Section F)

Wholesale and retail trade services; repair services of motor vehicles and motorcycles (Section G)

Transportation and storage (Section H)

Accommodation and food services (Section I)

Financial and insurance services (Section K): output of the central bank

Financial and insurance services (Section K): financial services in general

Financial services provided for direct payment

Financial services paid for through loading interest charges

Financial services consisting of acquiring and disposing of financial assets and liabilities in financial markets

Financial services provided in insurance and pension schemes, where activity is financed by loading insurance contributions and from the income return on savings

Real estate services (Section L)

Professional, scientific and technical services (Section M); administrative and support services (Section N)

Public administration and defence services, compulsory social security services (Section O)

Education services (Section P); human health and social work services (Section Q)

Arts, entertainment and recreation services (Section R); Other services (Section S)

Private households as employers (Section T)

INTERMEDIATE CONSUMPTION (P.2)

Time of recording and valuation of intermediate consumption

FINAL CONSUMPTION (P.3, P.4)

Final consumption expenditure (P.3)

Actual final consumption (P.4)

Time of recording and valuation of final consumption expenditure

Time of recording and valuation of actual final consumption

GROSS CAPITAL FORMATION (P.5)

Gross fixed capital formation (P.51g)

Time of recording and valuation of gross fixed capital formation

Consumption of fixed capital (P.51c)

Changes in inventories (P.52)

Time of recording and valuation of changes in inventories

Acquisitions less disposals of valuables (P.53)

EXPORTS AND IMPORTS OF GOODS AND SERVICES (P.6 AND P.7)

Exports and imports of goods (P.61 and P.71)

Exports and imports of services (P.62 and P.72)

TRANSACTIONS IN EXISTING GOODS

ACQUISITIONS LESS DISPOSALS OF NON-PRODUCED ASSETS (NP)

|

CHAPTER 4 |

DISTRIBUTIVE TRANSACTIONS |

COMPENSATION OF EMPLOYEES (D.1)

Wages and salaries (D.11)

Wages and salaries in cash

Wages and salaries in kind

Employers’ social contributions (D.12)

Employers’ actual social contributions (D.121)

Employers’ imputed social contributions (D.122)

TAXES ON PRODUCTION AND IMPORTS (D.2)

Taxes on products (D.21)

Value added type taxes (VAT) (D.211)

Taxes and duties on imports excluding VAT (D.212)

Taxes on products, except VAT and import taxes (D.214)

Other taxes on production (D.29)

Taxes on production and imports paid to the institutions of the European Union

Taxes on production and imports: time of recording and amounts to be recorded

SUBSIDIES (D.3)

Subsidies on products (D.31)

Import subsidies (D.311)

Other subsidies on products (D.319)

Other subsidies on production (D.39)

PROPERTY INCOME (D.4)

Interest (D.41)

Interest on deposits and loans

Interest on debt securities

Interest on bills and similar short-term instruments

Interest on bonds and debentures

Interest rate swaps and forward rate agreements

Interest on financial leases

Other interest

Time of recording

Distributed income of corporations (D.42)

Dividends (D.421)

Withdrawals from the income of quasi-corporations (D.422)

Reinvested earnings on foreign direct investment (D.43)

Other investment income (D.44)

Investment income attributable to insurance policy holders (D.441)

Investment income payable on pension entitlements (D.442)

Investment income attributable to collective investment fund shareholders (D.443)

Rent (D.45)

Rent on land

Rents on subsoil assets

CURRENT TAXES ON INCOME, WEALTH, ETC. (D.5)

Taxes on income (D.51)

Other current taxes (D.59)

SOCIAL CONTRIBUTIONS AND BENEFITS (D.6)

Net social contributions (D.61)

Employers’ actual social contributions (D.611)

Employers’ imputed social contributions (D.612)

Households’ actual social contributions (D.613)

Households’ social contribution supplements (D.614)

Social benefits other than social transfers in kind (D.62)

Social security benefits in cash (D.621)

Other social insurance benefits (D.622)

Social assistance benefits in cash (D.623)

Social transfers in kind (D.63)

Social transfers in kind — general government and NPISHs non-market production (D.631)

Social transfers in kind — market production purchased by general government and NPISHs (D.632)

OTHER CURRENT TRANSFERS (D.7)

Net non-life insurance premiums (D.71)

Non-life insurance claims (D.72)

Current transfers within general government (D.73)

Current international cooperation (D.74)

Miscellaneous current transfers (D.75)

Current transfers to NPISHs (D.751)

Current transfers between households (D.752)

Other miscellaneous current transfers (D.759)

Fines and penalties

Lotteries and gambling

Payments of compensation

VAT- and GNI-based EU own resources (D.76)

ADJUSTMENT FOR THE CHANGE IN PENSION ENTITLEMENTS (D.8)

CAPITAL TRANSFERS (D.9)

Capital taxes (D.91)

Investment grants (D.92)

Other capital transfers (D.99)

EMPLOYEE STOCK OPTIONS (ESOs)

|

CHAPTER 5 |

FINANCIAL TRANSACTIONS |

GENERAL FEATURES OF FINANCIAL TRANSACTIONS

Financial assets, financial claims, and liabilities

Contingent assets and contingent liabilities

Categories of financial assets and liabilities

Balance sheets, financial account, and other flows

Valuation

Net and gross recording

Consolidation

Netting

Accounting rules for financial transactions

A financial transaction with a current or a capital transfer as counterpart

A financial transaction with property income as counterpart

Time of recording

A from-whom-to-whom financial account

CLASSIFICATION OF FINANCIAL TRANSACTIONS BY CATEGORIES IN DETAIL

Monetary gold and special drawing rights (F.1)

Monetary gold (F.11)

SDRs (F.12)

Currency and deposits (F.2)

Currency (F.21)

Deposits (F.22 and F.29)

Transferable deposits (F.22)

Other deposits (F.29)

Debt securities (F.3)

Main features of debt securities

Classification by original maturity and currency

Classification by type of interest rate

Fixed interest rate debt securities

Variable interest rate debt securities

Mixed interest rate debt securities

Private placements

Securitisation

Covered bonds

Loans (F.4)

Main features of loans

Classification of loans by original maturity, currency, and purpose of lending

Distinction between transactions in loans and transactions in deposits

Distinction between transactions in loans and transactions in debt securities

Distinction between transactions in loans, trade credit and trade bills

Securities lending and repurchase agreements

Financial leases

Other types of loans

Financial assets excluded from the category of loans

Equity and investment fund shares or units (F.5)

Equity (F.51)

Depository receipts

Listed shares (F.511)

Unlisted shares (F.512)

Initial public offering, listing, de-listing, and share buy back

Financial assets excluded from equity securities

Other equity (F.519)

Valuation of transactions in equity

Investment fund shares or units (F.52)

MMF shares or units (F.521)

Non-MMF investment fund shares/units (F.522)

Valuation of transactions in investment fund shares or units

Insurance, pension and standardised guarantee schemes (F.6)

Non-life insurance technical reserves (F.61)

Life insurance and annuity entitlements (F.62)

Pension entitlements (F.63)

Contingent pension entitlements

Claims of pension funds on pension managers (F.64)

Entitlements to non-pension benefits (F.65)

Provisions for calls under standardised guarantees (F.66)

Standardised guarantees and one-off guarantees

Financial derivatives and employee stock options (F.7)

Financial derivatives (F.71)

Options

Forwards

Options vis-à-vis forwards

Swaps

Forward rate agreements (FRAs)

Credit derivatives

Credit default swaps

Financial instruments not included in financial derivatives

Employee stock options (F.72)

Valuation of transactions in financial derivatives and employee stock options

Other accounts receivable/payable (F.8)

Trade credits and advances (F.81)

Other accounts receivable/payable, excluding trade credits and advances (F.89)

|

ANNEX 5.1 — |

CLASSIFICATION OF FINANCIAL TRANSACTIONS |

Classification of financial transactions by category

Classification of financial transactions by negotiability

Structured securities

Classification of financial transactions by type of income

Classification of financial transactions by type of interest rate

Classification of financial transactions by maturity

Short-term and long-term maturity

Original maturity and remaining maturity

Classification of financial transactions by currency

Measures of money

|

CHAPTER 6 |

OTHER FLOWS |

INTRODUCTION

OTHER CHANGES IN ASSETS AND LIABILITIES

Other changes in the volume of assets and liabilities (K.1 to K.6)

Economic appearance of assets (K.1)

Economic disappearance of non-produced assets (K.2)

Catastrophic losses (K.3)

Uncompensated seizures (K.4)

Other changes in volume not elsewhere classified (K.5)

Changes in classification (K.6)

Changes in sector classification and institutional unit structure (K.61)

Changes in classification of assets and liabilities (K.62)

Nominal holding gains and losses (K.7)

Neutral holding gains and losses (K.71)

Real holding gains and losses (K.72)

Holding gains and losses by types of financial asset and liability

Monetary gold and SDRs (AF.1)

Currency and deposits (AF.2)

Debt securities (AF.3)

Loans (AF.4)

Equity and investment fund shares (AF.5)

Insurance, pension and standardised guarantee schemes (AF.6)

Financial derivatives and employee stock options (AF.7)

Other accounts receivable/payable (AF.8)

Assets denominated in foreign currency

|

CHAPTER 7 |

BALANCE SHEETS |

TYPES OF ASSETS AND LIABILITIES

Definition of an asset

EXCLUSIONS FROM THE ASSET AND LIABILITY BOUNDARY

CATEGORIES OF ASSETS AND LIABILITIES

Produced non-financial assets (AN.1)

Non-produced non-financial assets (AN.2)

Financial assets and liabilities (AF)

VALUATION OF ENTRIES IN THE BALANCE SHEETS

General valuation principles

NON-FINANCIAL ASSETS (AN)

Produced non-financial assets (AN.1)

Fixed assets (AN.11)

Intellectual property products (AN.117)

Costs of ownership transfer on non-produced assets (AN.116)

Inventories (AN.12)

Valuables (AN.13)

Non-produced non-financial assets (AN.2)

Natural resources (AN.21)

Land (AN.211)

Mineral and energy reserves (AN.212)

Other natural assets (AN.213, AN.214 and AN.215)

Contracts, leases and licences (AN.22)

Purchases less sales of goodwill and marketing assets (AN.23)

FINANCIAL ASSETS AND LIABILITIES (AF)

Monetary gold and SDRs (AF.1)

Currency and deposits (AF.2)

Debt securities (AF.3)

Loans (AF.4)

Equity and investment fund shares/units (AF.5)

Insurance, pension and standardised guarantee schemes (AF.6)

Financial derivatives and employee stock options (AF.7)

Other accounts receivable/payable (AF.8)

FINANCIAL BALANCE SHEETS

MEMORANDUM ITEMS

Consumer durables (AN.m)

Foreign direct investment (AF.m1)

Non-performing loans (AF.m2)

Recording of non-performing loans

|

ANNEX 7.1 |

SUMMARY OF EACH ASSET CATEGORY |

|

ANNEX 7.2 |

A MAP OF ENTRIES FROM OPENING BALANCE SHEET TO CLOSING BALANCE SHEET |

|

CHAPTER 8 |

THE SEQUENCE OF ACCOUNTS |

INTRODUCTION

The sequence of accounts

SEQUENCE OF ACCOUNTS

Current accounts

Production account (I)

Distribution and use of income accounts (II)

Primary distribution of income accounts (II.1)

Generation of income account (II.1.1)

Allocation of primary income account (II.1.2)

Entrepreneurial income account (II.1.2.1)

Allocation of other primary income account (II.1.2.2)

Secondary distribution of income account (II.2)

Redistribution of income in kind account (II.3)

Use of income account (II.4)

Use of disposable income account (II.4.1)

Use of adjusted disposable income account (II.4.2)

Accumulation accounts (III)

Capital account (III.1)

Change in net worth due to saving and capital transfers account (III.1.1)

Acquisitions of non-financial assets account (III.1.2)

Financial account (III.2)

Other changes in assets account (III.3)

Other changes in volume of assets account (III.3.1)

Revaluation account (III.3.2)

Neutral holding gains and losses account (III.3.2.1)

Real holding gains and losses account (III.3.2.2)

Balance sheets (IV)

Opening balance sheet (IV.1)

Changes in balance sheet (IV.2)

Closing balance sheet (IV.3)

REST OF THE WORLD ACCOUNTS (V)

Current accounts

External account of goods and services (V.I)

External account of primary incomes and current transfers (V.II)

External accumulation accounts (V.III)

Capital account (V.III.1)

Financial account (V.III.2)

Other changes in assets account (V.III.3)

Balance sheets (V.IV)

GOODS AND SERVICES ACCOUNT (0)

INTEGRATED ECONOMIC ACCOUNTS

AGGREGATES

Gross domestic product at market prices (GDP)

Operating surplus of the total economy

Mixed income of the total economy

Entrepreneurial income of the total economy

National income (at market prices)

National disposable income

Saving

Current external balance

Net lending (+) or borrowing (-) of the total economy

Net worth of the total economy

General government expenditure and revenue

|

CHAPTER 9 |

SUPPLY AND USE TABLES AND THE INPUT-OUTPUT FRAMEWORK |

INTRODUCTION

DESCRIPTION

STATISTICAL TOOL

TOOL FOR ANALYSIS

SUPPLY AND USE TABLES IN MORE DETAIL

Classifications

Valuation principles

Trade and transport margins

Taxes less subsidies on production and imports

Other basic concepts

Supplementary information

DATA SOURCES AND BALANCING

TOOL FOR ANALYSIS AND EXTENSIONS

|

CHAPTER 10 |

PRICE AND VOLUME MEASURES |

SCOPE OF PRICE AND VOLUME INDICES IN THE NATIONAL ACCOUNTS

The integrated system of price and volume indices

Other price and volume indices

GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF MEASURING PRICE AND VOLUME INDICES

Definition of prices and volumes of market products

Quality, price and homogeneous products

Prices and volume

New products

Principles for non-market services

Principles for value added and GDP

SPECIFIC PROBLEMS IN THE APPLICATION OF THE PRINCIPLES

Taxes and subsidies on products and imports

Other taxes and subsidies on production

Consumption of fixed capital

Compensation of employees

Stocks of produced fixed assets and inventories

MEASURES OF REAL INCOME FOR THE TOTAL ECONOMY

INTERSPATIAL PRICE AND VOLUME INDICES

|

CHAPTER 11 |

POPULATION AND LABOUR INPUTS |

TOTAL POPULATION

ECONOMICALLY ACTIVE POPULATION

EMPLOYMENT

Employees

Self-employed persons

Employment and residence

UNEMPLOYMENT

JOBS

Jobs and residence

THE NON-OBSERVED ECONOMY

TOTAL HOURS WORKED

Specifying hours actually worked

FULL-TIME EQUIVALENCE

EMPLOYEE LABOUR INPUT AT CONSTANT COMPENSATION

PRODUCTIVITY MEASURES

|

CHAPTER 12 |

QUARTERLY NATIONAL ACCOUNTS |

INTRODUCTION

SPECIFIC FEATURES OF QUARTERLY NATIONAL ACCOUNTS

Time of recording

Work-in-progress

Activities concentrated in specific periods within a year

Low-frequency payments

Flash estimates

Balancing and benchmarking of quarterly national accounts

Balancing

Consistency between quarterly and annual accounts — benchmarking

Chain-linked measures of price and volume changes

Seasonal and calendar adjustments

Sequence of compilation of seasonally adjusted chain-linked volume measures

|

CHAPTER 13 |

REGIONAL ACCOUNTS |

INTRODUCTION

REGIONAL TERRITORY

UNITS AND REGIONAL ACCOUNTS

Institutional units

Local kind-of-activity units and regional production activities by industry

METHODS OF REGIONALISATION

AGGREGATES FOR PRODUCTION ACTIVITIES

Gross value added and gross domestic product by region

The allocation of FISIM to user industries

Employment

Compensation of employees

Transition from regional GVA to regional GDP

Volume growth rates of regional GVA

REGIONAL HOUSEHOLD INCOME ACCOUNTS

|

CHAPTER 14 |

FINANCIAL INTERMEDIATION SERVICES INDIRECTLY MEASURED (FISIM) |

THE CONCEPT OF FISIM AND THE IMPACT OF THEIR USER ALLOCATION ON MAIN AGGREGATES

CALCULATION OF FISIM OUTPUT BY SECTORS S.122 AND S.125

Statistical data required

Reference rates

Internal reference rate

External reference rates

Detailed breakdown of FISIM by institutional sector

Breakdown into intermediate and final consumption of FISIM allocated to households

CALCULATION OF IMPORTS OF FISIM

FISIM IN VOLUME TERMS

CALCULATION OF FISIM BY INDUSTRY

THE OUTPUT OF THE CENTRAL BANK

|

CHAPTER 15 |

CONTRACTS, LEASES AND LICENCES |

INTRODUCTION

THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN OPERATING LEASES, RESOURCE LEASES AND FINANCIAL LEASES

Operating leases

Financial leases

Resource leases

Permits to use a natural resource

Permits to undertake specific activities

Public-private partnerships (PPPs)

Service concession contracts

Marketable operating leases (AN.221)

Entitlements to future goods and services on an exclusive basis (AN.224)

|

CHAPTER 16 |

INSURANCE |

INTRODUCTION

Direct insurance

Reinsurance

The units involved

OUTPUT OF DIRECT INSURANCE

Premiums earned

Premium supplements

Adjusted claims incurred and benefits due

Non-life insurance adjusted claims incurred

Life insurance benefits due

Insurance technical reserves

Defining insurance output

Non-life insurance

Life insurance

Reinsurance

TRANSACTIONS ASSOCIATED WITH NON-LIFE INSURANCE

Allocation of insurance output among users

Insurance services provided to and from the rest of the world

The accounting entries

TRANSACTIONS OF LIFE INSURANCE

TRANSACTIONS ASSOCIATED WITH REINSURANCE

TRANSACTIONS ASSOCIATED WITH INSURANCE AUXILIARIES

ANNUITIES

RECORDING NON-LIFE INSURANCE CLAIMS

Treatment of adjusted claims

Treatment of catastrophic losses

|

CHAPTER 17 |

SOCIAL INSURANCE INCLUDING PENSIONS |

INTRODUCTION

Social insurance schemes, social assistance and individual insurance policies

Social benefits

Social benefits provided by general government

Social benefits provided by other institutional units

Pensions and other forms of benefit

SOCIAL INSURANCE BENEFITS OTHER THAN PENSIONS

Social security schemes other than pension schemes

Other employment-related social insurance schemes

Recording of stocks and flows by type of non-pension social insurance scheme

Social security schemes

Other employment-related non-pension social insurance schemes

PENSIONS

Types of pension schemes

Social security pension schemes

Other employment-related pension schemes

Defined contribution schemes

Defined benefit schemes

Notional defined contribution schemes and hybrid schemes

Defined benefit schemes as compared to defined contribution schemes

Pension administrator, pension manager, pension fund and multi-employer pension scheme

Recording of stocks and flows by type of pension scheme in social insurance

Transactions for social security pension schemes

Transactions for other employment-related pension schemes

Transactions for defined contribution pension schemes

Other flows related to defined contribution pension schemes

Transactions for defined benefit pension schemes

SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE FOR ACCRUED-TO-DATE PENSION ENTITLEMENTS IN SOCIAL INSURANCE

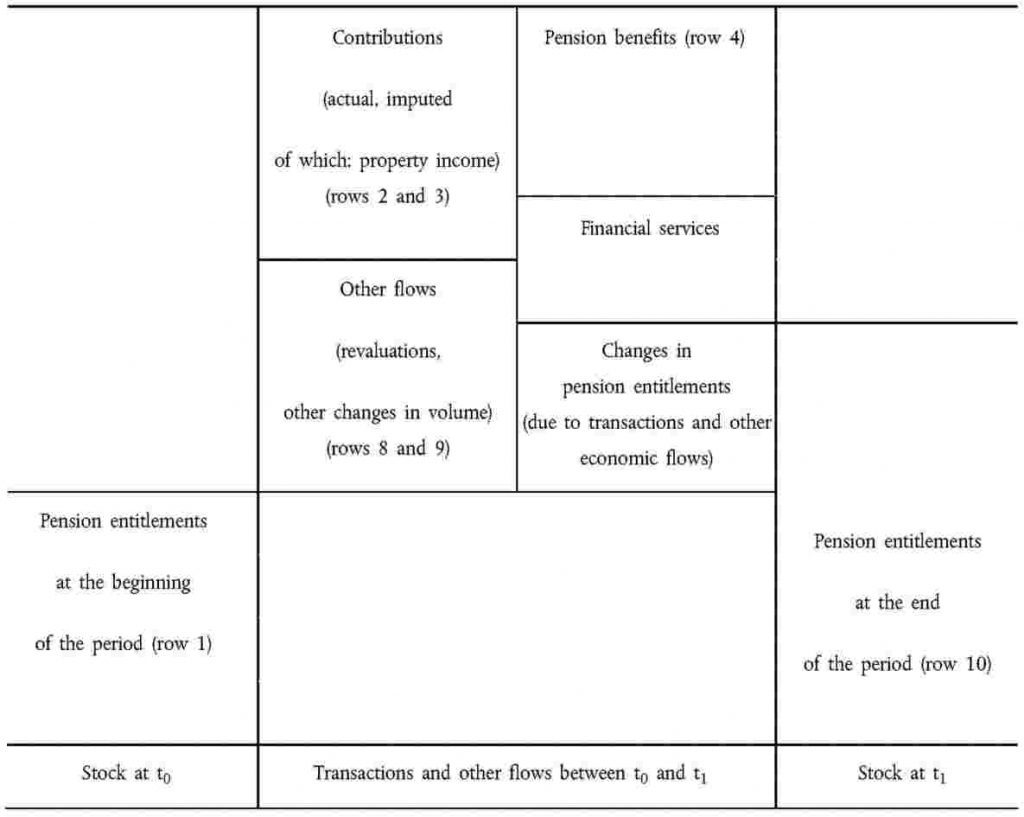

Design of the supplementary table

The columns of the table

The rows of the table

Opening and closing balance sheets

Changes in pension entitlements due to transactions

Changes to pension entitlements due to other economic flows

Related indicators

Actuarial assumptions

Accrued-to-date entitlements

Discount rate

Wage growth

Demographic assumptions

|

CHAPTER 18 |

REST OF THE WORLD ACCOUNTS |

INTRODUCTION

ECONOMIC TERRITORY

Residence

INSTITUTIONAL UNITS

BRANCHES AS A TERM USED IN THE INTERNATIONAL ACCOUNTS OF THE BALANCE OF PAYMENTS

NOTIONAL RESIDENT UNITS

MULTI-TERRITORY ENTERPRISES

GEOGRAPHICAL BREAKDOWN

THE INTERNATIONAL ACCOUNTS OF THE BALANCE OF PAYMENTS

BALANCING ITEMS IN THE CURRENT ACCOUNTS OF THE INTERNATIONAL ACCOUNTS

THE ACCOUNTS FOR THE REST OF THE WORLD SECTOR AND THEIR RELATIONSHIP WITH THE INTERNATIONAL ACCOUNTS OF THE BALANCE OF PAYMENTS

The external account of goods and services

Valuation

Goods for processing

Merchanting

Goods under merchanting

Imports and exports of FISIM

The external account of primary and secondary income

The primary income account

Direct investment income

The secondary income (current transfers) account of the BPM6

The external capital account

The external financial account and international investment position (IIP)

BALANCE SHEETS FOR THE REST OF THE WORLD SECTOR

|

CHAPTER 19 |

EUROPEAN ACCOUNTS |

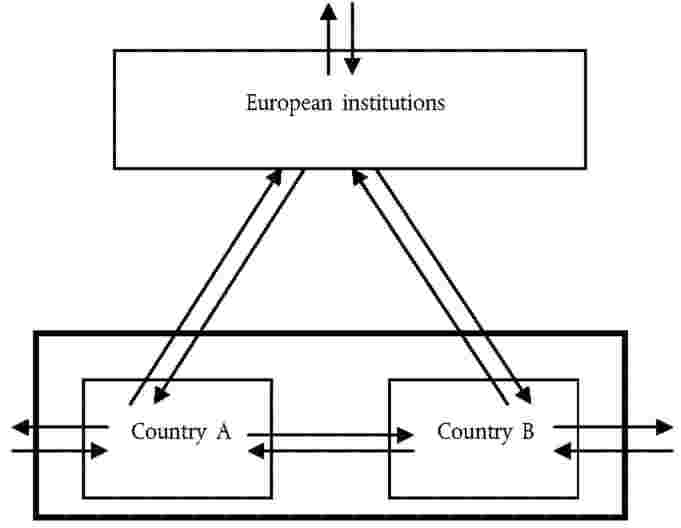

INTRODUCTION

FROM NATIONAL TO EUROPEAN ACCOUNTS

Conversion of data in different currencies

European institutions

The rest of the world account

Balancing of transactions

Price and volume measures

Balance sheets

‧From whom-to-whom‧ matrices

|

ANNEX 19.1. — |

THE ACCOUNTS OF EUROPEAN INSTITUTIONS |

Resources

Uses

Consolidation

|

CHAPTER 20 |

THE GOVERNMENT ACCOUNTS |

INTRODUCTION

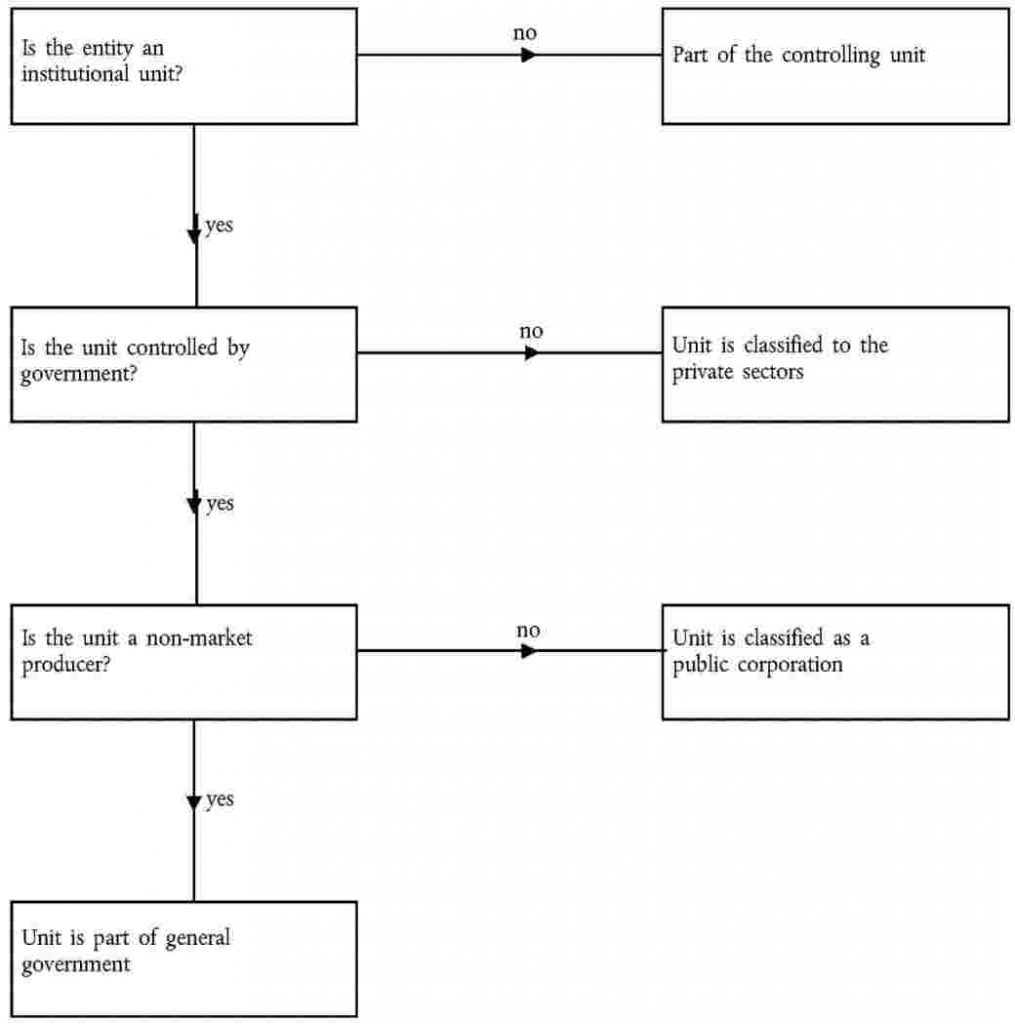

DEFINING THE GENERAL GOVERNMENT SECTOR

Identification of units in the government

Government units

NPIs classified to the general government sector

Other units of general government

Public control

Market/non-market delineation

Notion of economically significant prices

Criteria of the purchaser of the output of a public producer

The output is sold primarily to corporations and households

The output is sold only to government

The output is sold to government and others

The market/non-market test

Financial intermediation and the government boundary

Borderline cases

Public head offices

Pension funds

Quasi-corporations

Restructuring agencies

Privatisation agencies

Defeasances structures

Special purpose entities

Joint ventures

Market regulatory agencies

Supranational authorities

The subsectors of general government

Central government

State government

Local government

Social security funds

THE GOVERNMENT FINANCE PRESENTATION OF STATISTICS

Framework

Revenue

Taxes and social contributions

Sales

Other revenue

Expenditure

Compensation of employees and intermediate consumption

Social benefits expenditure

Interest

Other current expenditure

Capital expenditure

Link with government final consumption expenditure (P.3)

Government expenditure by function (COFOG)

Balancing items

The net lending/net borrowing (B.9)

Changes in net worth due to saving and capital transfers (B.101)

Financing

Transactions in assets

Transactions in liabilities

Other economic flows

Revaluation account

Other changes in volume of assets account

Balance sheets

Consolidation

ACCOUNTING ISSUES RELATING TO GENERAL GOVERNMENT

Tax revenue

Character of tax revenue

Tax credits

Amounts to record

Amounts uncollectible

Time of recording

Accrual recording

Accrual recording of taxes

Interest

Discounted and zero-coupon bonds

Index-linked securities

Financial derivatives

Court decisions

Military expenditure

Relations of general government with public corporations

Equity investment in public corporations and distribution of earnings

Equity investment

Capital injections

Subsidies and capital injections

Rules applicable to particular circumstances

Fiscal operations

Public corporations distributions

Dividends versus withdrawal of equity

Taxes versus withdrawal of equity

Privatisation and nationalisation

Privatisation

Indirect privatisations

Nationalisation

Transactions with the central bank

Restructures, mergers, and reclassifications

Debt operations

Debt assumptions, debt cancellation and debt write-offs

Debt assumption and cancellation

Debt assumption involving a transfer of non-financial assets

Debt write-offs or write-downs

Other debt restructuring

Purchase of debt above the market value

Defeasances and bailouts

Debt guarantees

Derivatives-type guarantees

Standardised guarantees

One-off guarantees

Securitisation

Definition

Criteria for sale recognition

Recording of flows

Other issues

Pension obligations

Lump sum payments

Public-private partnerships

Scope of PPPs

Economic ownership and allocation of the asset

Accounting issues

Transactions with international and supranational organisations

Development assistance

THE PUBLIC SECTOR

Public sector control

Central banks

Public quasi-corporations

Special purpose entities and non-residents

Joint ventures

|

CHAPTER 21 |

LINKS BETWEEN BUSINESS ACCOUNTS AND NATIONAL ACCOUNTS AND THE MEASUREMENT OF CORPORATE ACTIVITY |

SOME SPECIFIC RULES AND METHODS OF BUSINESS ACCOUNTING

Time of recording

Double entry and quadruple entry accounting

Valuation

Income statement and balance sheet

NATIONAL ACCOUNTS AND BUSINESS ACCOUNTS: PRACTICAL ISSUES

THE TRANSITION FROM BUSINESS ACCOUNTS TO NATIONAL ACCOUNTS: THE EXAMPLE OF NON-FINANCIAL ENTERPRISES

Conceptual adjustments

Adjustments to achieve consistency with the accounts of other sectors

Examples of adjustments for exhaustiveness

SPECIFIC ISSUES

Holding gains/losses

Globalisation

Mergers and acquisitions

|

CHAPTER 22 |

SATELLITE ACCOUNTS |

INTRODUCTION

Functional classifications

MAJOR CHARACTERISTICS OF SATELLITE ACCOUNTS

Functional satellite accounts

Special sector accounts

Inclusion of non-monetary data

Extra detail and supplementary concepts

Different basic concepts

Use of modelling and inclusion of experimental results

Designing and compiling satellite accounts

NINE SPECIFIC SATELLITE ACCOUNTS

Agricultural accounts

Environmental accounts

Health accounts

Household production accounts

Labour accounts and SAM

Productivity and growth accounts

Research and development accounts

Social protection accounts

Tourism satellite accounts

|

CHAPTER 23 |

CLASSIFICATIONS |

INTRODUCTION

CLASSIFICATION OF INSTITUTIONAL SECTORS (S)

CLASSIFICATION OF TRANSACTIONS AND OTHER FLOWS

Transactions in products (P)

Transactions in non-produced non-financial assets (NP codes)

Distributive transactions (D)

Current transfers in cash and kind (D.5-D.8)

Transactions in financial assets and liabilities (F)

Other changes in assets (K)

CLASSIFICATION OF BALANCING ITEMS AND NET WORTH (B)

CLASSIFICATION OF BALANCE SHEET ENTRIES (L)

CLASSIFICATION OF ASSETS (A)

Non-financial assets (AN)

Financial assets (AF)

CLASSIFICATION OF SUPPLEMENTARY ITEMS

Non-performing loans

Capital services

Pensions table

Consumer durables

Foreign direct investment

Contingent positions

Currency and deposits

Classification of debt securities according to outstanding maturity

Listed and unlisted debt securities

Long-term loans with outstanding maturity of less than one year and long-term loans secured by mortgage

Listed and unlisted investment shares

Arrears in interest and repayments

Personal and total remittances

REGROUPING AND CODING OF INDUSTRIES (A) AND PRODUCTS (P)

CLASSIFICATION OF THE FUNCTIONS OF THE GOVERNMENT (COFOG)

CLASSIFICATION OF INDIVIDUAL CONSUMPTION BY PURPOSE (Coicop)

CLASSIFICATION OF THE PURPOSES OF NON-PROFIT INSTITUTIONS SERVING HOUSEHOLDS (COPNI)

CLASSIFICATION OF OUTLAYS OF PRODUCERS BY PURPOSE (COPP)

|

CHAPTER 24 |

THE ACCOUNTS |

|

Table 24.1 |

Account 0: Goods and services account |

|

Table 24.2 |

Full sequence of accounts for the total economy |

|

Table 24.3 |

Full sequence of accounts for non-financial corporations |

|

Table 24.4 |

Full sequence of accounts for financial corporations |

|

Table 24.5 |

Full sequence of accounts for general government |

|

Table 24.6 |

Full sequence of accounts for households |

|

Table 24.7 |

Full sequence of accounts for non-profit institutions serving households |

CHAPTER 1

GENERAL FEATURES AND BASIC PRINCIPLES

GENERAL FEATURES

|

1.01 |

The European System of Accounts (hereinafter referred to as ‧the ESA 2010‧ or ‧the ESA‧) is an internationally compatible accounting framework for a systematic and detailed description of a total economy (that is, a region, country or group of countries), its components and its relations with other total economies. |

|

1.02 |

The predecessor of the ESA 2010, the European System of Accounts 1995 (the ESA 95), was published in 1996 (1). The ESA 2010 methodology as set out in this Annex has the same structure as the ESA 95 publication for the first thirteen chapters, but then has eleven new chapters elaborating aspects of the system which reflect developments in measuring modern economies, or in the use of the ESA 95 in the European Union (the EU). |

|

1.03 |

The structure of this manual is as follows. Chapter 1 covers the basic features of the system in terms of concepts, and sets out the principles of the ESA and describes the fundamental statistical units and their groupings. It gives an overview of the sequence of accounts, and a brief description of key aggregates and the role of supply and use tables and the input-output framework. Chapter 2 describes the institutional units used in measuring the economy, and how these units are classified into sectors and other groups to allow analysis. Chapter 3 describes all transactions with regard to products (goods and services), as well as non-produced assets, in the system. Chapter 4 describes all the transactions in the economy which distribute and re-distribute income and wealth in the economy. Chapter 5 describes the financial transactions in the economy. Chapter 6 describes the changes that can occur to the value of assets through non-economic events or price changes. Chapter 7 describes balance sheets, and the asset and liability classification scheme. Chapter 8 sets out the sequence of accounts, and the balancing items associated with each account. Chapter 9 describes supply and use tables, and their role in reconciling the measures of income, output and expenditure in the economy. It also describes the input-output tables that can be derived from the supply and use tables. Chapter 10 describes the conceptual basis for the price and volume measures associated with the nominal values found in the accounts. Chapter 11 describes the population and labour market measures which can be used with measures of the national accounts in economic analysis. Chapter 12 gives a brief description of quarterly national accounts, and how they differ in emphasis from the annual accounts. |

|

1.04 |

Chapter 13 describes the purposes, concepts and compilation issues in drawing up a set of regional accounts. Chapter 14 covers the measurement of financial services provided by financial intermediaries and funded through net interest receipts, and reflects years of research and development by Member States in order to have a measure which is robust and harmonised across Member States. Chapter 15 on contracts, leases and licences is necessary to describe an area of increasing importance in the national accounts. Chapters 16 and 17 on insurance, social insurance and pensions describe how these arrangements are handled in the national accounts, as questions of redistribution become of increasing interest as populations age. Chapter 18 covers the rest of the world accounts, which are the national accounts equivalent to the accounts of the balance of payments measuring system. Chapter 19 on European Accounts is also new, covering aspects of the national accounts where European institutional and trading arrangements raise issues which require a harmonised approach. Chapter 20 describes the accounts for the government sector — an area of special interest as issues of fiscal prudence by Member States continue to be critical in the conduct of economic policy in the EU. Chapter 21 describes the links between business accounts and national accounts, an area of growing interest as multinational corporations become responsible for an increasing share in gross domestic product (GDP) for all countries. Chapter 22 describes the relationship of satellite accounts with the main national accounts. Chapters 23 and 24 are for reference purposes; Chapter 23 sets out the classifications used for sectors, activities and products in the ESA 2010, and Chapter 24 sets out the complete sequence of accounts for every sector. |

|

1.05 |

The structure of the ESA 2010 is consistent with the worldwide guidelines on national accounting set out in the System of National Accounts 2008 (2008 SNA), apart from certain differences in presentation and the higher degree of precision of some of the ESA 2010 concepts which are used for specific EU purposes. Those guidelines were produced under the joint responsibility of the United Nations (UN), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Statistical Office of the European Union (Eurostat), the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the World Bank. The ESA 2010 is focused on the circumstances and data needs in the EU. Like the 2008 SNA, the ESA 2010 is harmonised with the concepts and classifications used in many other social and economic statistics (for example, statistics on employment, statistics on manufacturing and statistics on external trade). The ESA 2010 therefore serves as the central framework of reference for the social and economic statistics of the EU and its Member States. |

|

1.06 |

The ESA framework consists of two main sets of tables:

|

|

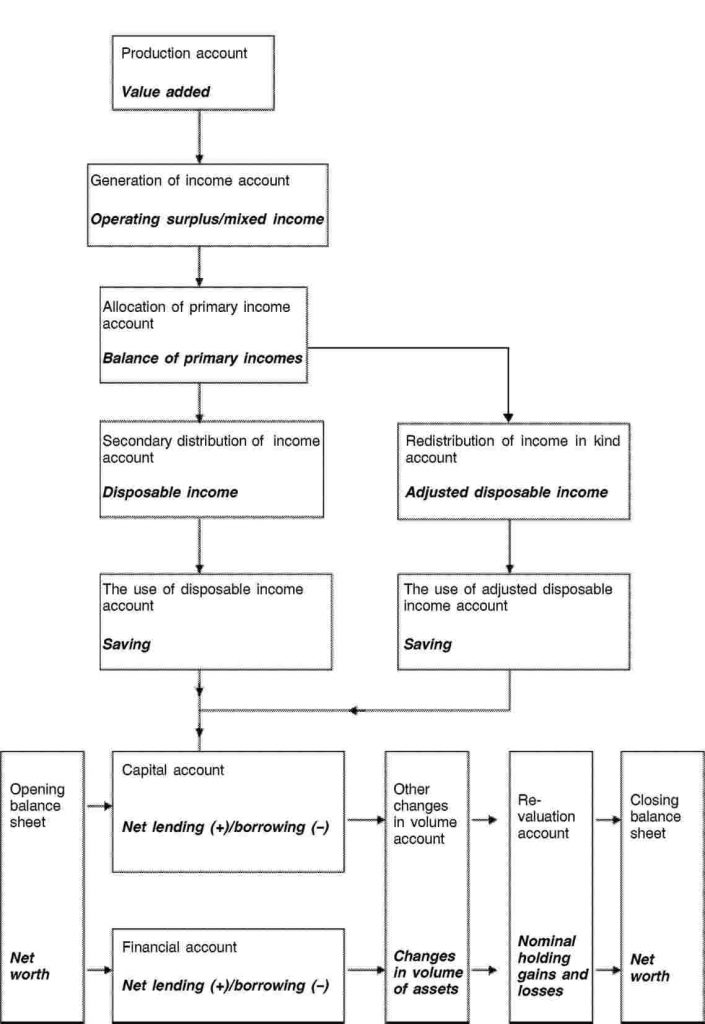

1.07 |

The sector accounts provide, by institutional sector, a systematic description of the different stages of the economic process: production, generation of income, distribution of income, redistribution of income, use of income and financial and non-financial accumulation. The sector accounts also include balance sheets to describe the stocks of assets, liabilities and net worth at the beginning and the end of the accounting period. |

|

1.08 |

The input-output framework, through the supply and use tables, sets out in more detail the production process (cost structure, income generated and employment) and the flows of goods and services (output, imports, exports, final consumption, intermediate consumption and capital formation by product group). Two important accounting identities are reflected in this framework: the sum of incomes generated in an industry is equal to the value added produced by that industry; and, for any product or grouping of products, supply is equal to demand. |

|

1.09 |

The ESA 2010 encompasses concepts of population and employment. Such concepts are relevant for the sector accounts, the accounts by industry and the supply and use framework. |

|

1.10 |

The ESA 2010 is not restricted to annual national accounting, but applies also to quarterly and shorter or longer period accounts. It also applies to regional accounts. |

|

1.11 |

The ESA 2010 exists alongside the 2008 SNA because of the uses of national accounts measures in the EU. The Member States are responsible for the collection and presentation of their own national accounts to describe the economic situation of their countries. Member States also compile a set of accounts which are submitted to the Commission (Eurostat) as part of a regulatory data transmission programme, for key social, economic and fiscal policy uses in the Union. Those uses include determination of Member State monetary contributions to the EU budget via the ‧fourth resource‧, aid to regions of the EU through the structural funds programme and surveillance of Member States’ economic performance in the framework of the excessive deficit procedure and of the Stability and Growth Pact. |

|

1.12 |

In order that levies and benefits are distributed according to measures compiled and presented in a strictly consistent manner, the economic statistics used for those purposes shall be compiled according to the same concepts and rules. The ESA 2010 is a regulation setting forth the rules, conventions, definitions and classifications to be applied in producing the national accounts in Member States which are to be part of the data transmission programme as set out in Annex B to this Regulation. |

|

1.13 |

Given the very large sums of money involved in the contributions and benefits system operated in the EU, it is essential that the measurement system be applied consistently in each Member State. In such circumstances, it is important to adopt a cautious approach to estimates which cannot be observed directly in the market place, avoiding the use of model-based procedures for the estimation of measures in the national accounts. |

|

1.14 |

The ESA 2010 concepts are in several instances more specific and precise than those of the 2008 SNA in order to ensure as much consistency as possible between Member States measures derived from the national accounts. This over-riding requirement for robust consistent estimates has resulted in the identification of a core set of national accounts in the EU. Where the level of consistency of measurement across Member States is insufficient, the latter estimates are generally included in so-called ‧non-core-accounts‧ covering supplementary tables and satellite accounts. |

|

1.15 |

An example of where it has been considered necessary to be cautious in the design of the ESA 2010 lies in the field of pension liabilities. The case for measuring these to assist in economic analyses is a strong one, but the critical requirement in the EU to produce accounts which are consistent across time and space has obliged a cautious approach. |

Globalisation

|

1.16 |

The increasingly global nature of economic activity has increased international trade in all its forms, and increased the challenges to countries of recording their domestic economies in the national accounts. Globalisation is the dynamic and multidimensional process whereby national resources become more internationally mobile, while national economies become increasingly interdependent. The feature of globalisation which potentially causes most measurement problems for national accounts is the increasing share of international transactions undertaken by multinational companies, where the transactions across borders are between parents, subsidiaries and affiliates. However other challenges exist, and a more exhaustive list of data issues is as follows:

|

|

1.17 |

All of these increasingly common aspects of globalisation make the capture and accurate measurement of cross-border flows a growing challenge for national statisticians. Even with a comprehensive and robust collection and measurement system for the entries in the rest of the world sector (and thus also in the international accounts found in the balance of payments), globalisation will increase the need for extra efforts to maintain the quality of national accounts for all economies and groupings of economies. |

USES OF THE ESA 2010

Framework for analysis and policy

|

1.18 |

The ESA framework can be used to analyse and evaluate:

|

|

1.19 |

For the EU and its Member States, the figures from the ESA framework play a major role in formulating and monitoring their social and economic policies. The following examples demonstrate uses of the ESA framework:

|

Characteristics of the ESA 2010 concepts

|

1.20 |

In order to establish a balance between data needs and data possibilities, the concepts in the ESA 2010 have several important characteristics. The characteristics are that the accounts are:

|

|

1.21 |

The concepts in the ESA 2010 are internationally compatible because:

|

|

1.22 |