Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the regimes applicable to those who wish to enter the territory of a European state. Furthermore, it sets out the main parameters that states have to respect under ECHR law as well as under EU law when impos- ing conditions for access to the territory or when carrying out border management activities.

As a general rule, states have a sovereign right to control the entry and continued presence of non-nationals in their territory. Both EU law and the ECHR impose some limits on this exercise of sovereignty. Nationals have the right to enter their own country, and EU nationals have a general right under EU law to enter other EU Mem- ber States. In addition, as explained in the following paragraphs, both EU law and the ECHR prohibit the rejection at borders of persons at risk of persecution or other seri- ous harm (principle of non-refoulement).

Under EU law, common rules exist for EU Member States regarding the issuance of short-term visas and the implementation of border control and border surveillance activities. The EU has also set up rules to prevent irregular entry. The EU agency Frontex was created in 2004 to support EU Member States in the management of external EU borders.[16] The agency also provides operational support through joint operations at land, air or sea borders. Under certain conditions, EU Member States can request Frontex to deploy a rapid intervention system known as RABIT.[17] When acting in the context of a Frontex or RABIT operation, EU Member States main- tain responsibility for their acts and omissions. In October 2011, Regulation (EU) No. 1168/2011 amending Regulation (EC) No. 2007/2004, which had established Frontex, strengthened the fundamental rights obligations incumbent on Frontex. In 2013, the Eurosur Regulation (Regulation (EU) No. 1052/2013) established a Euro- pean border surveillance system.

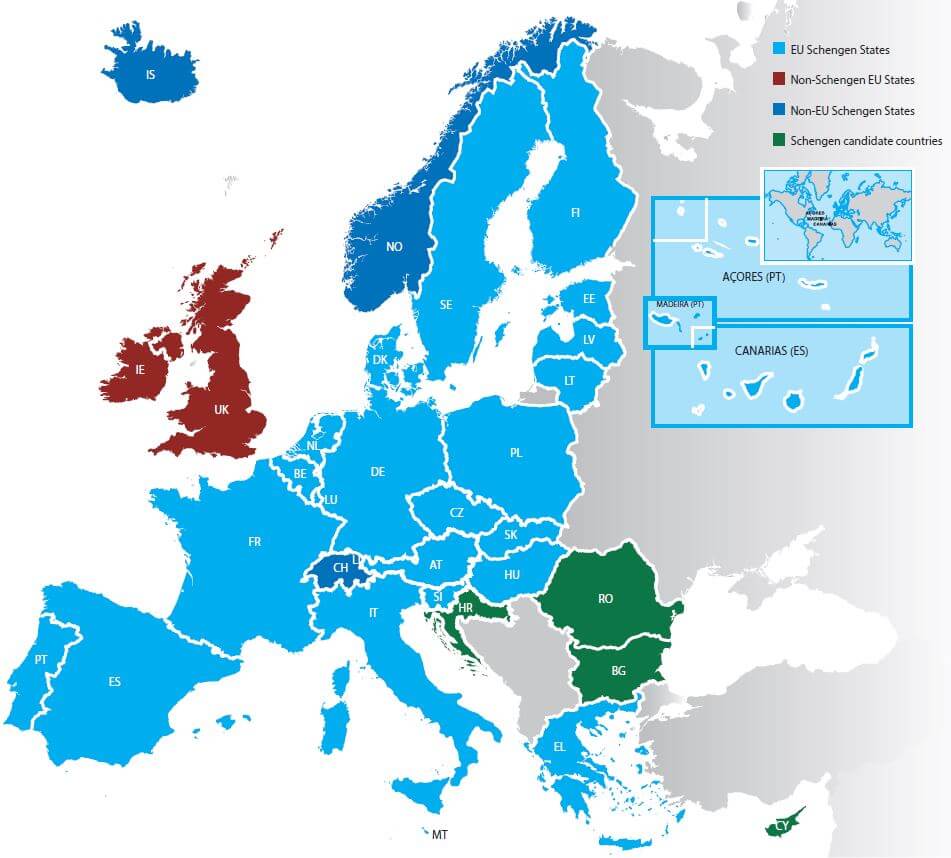

As illustrated in Figure 1, the Schengen acquis applies in full to most EU Member States. It establishes a unified system for maintaining external border controls and allows individuals to travel freely across borders within the Schengen area. Not all EU Member States are parties to the Schengen area and the Schengen system extends beyond the borders of the EU to Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Swit- zerland. Article 6 of the Schengen Borders Code (Regulation (EC) No. 562/2006) pro- hibits the application of the code in a way which amounts to refoulement or unlaw- ful discrimination.

Under the ECHR, states have the right as a matter of well-established international law and subject to their treaty obligations (including the ECHR) to control the entry, residence and expulsion of non-nationals. Access to the territory for non-nationals is not expressly regulated in the ECHR, nor does it say who should receive a visa. ECtHR case law only imposes certain limitations on the right of states to turn some- one away from their borders, for example, where this would amount to refoule- ment. The case law may, under certain circumstances, require states to allow the entry of an individual when it is a pre-condition for his or her exercise of certain Convention rights, in particular the right to respect for family life.[18]

1.1. The Schengen visa regime

EU nationals and nationals from those countries that are part of the Schengen area and their family members have the right to enter the territory of EU Member States without prior authorisation. They can only be excluded on grounds of public policy, public security or public health.

Under EU law, nationals from countries listed in the Annex 1 to the Visa List Regu- lation (Regulation (EC) No. 539/2001, note also amendments) can access the ter- ritory of the EU with a visa issued prior to entry. The Annex to the Regulation is

regularly amended. The webpage of the European Commission contains an up to date map with visa requirements for the Schengen area.[19] Turkish nationals, who were not subject to a visa requirement at the time of the entry into force of the pro- visions of the standstill clause, cannot be made subject to a visa requirement in EU Member States.[20]

Figure 1: Schengen area

Source: European Commission, Directorate-General of Home Affairs, 2013

Personal information on short-term visa applicants is stored in the Visa Informa- tion System (VIS Regulation (EC) No. 767/2008 as amended by Regulation (EC) No. 81/2009), a central IT system which connects consulates and external border crossing points.

Visits for up to three months in states that are part of the Schengen area are subject to the Visa Code (Regulation (EC) No. 810/2009, note also amendments). In con- trast, longer stays are the responsibility of individual states, which can regulate this in their domestic law. Nationals who are exempted from a mandatory visa under the Visa List Regulation (Regulation (EC) No. 539/2001) may require visas prior to their visit if coming for purposes other than a short visit. All mandatory visas must be obtained before travelling. Only specific categories of third-country nationals are exempt from this requirement.

Example: In the Koushkaki case,[21] the CJEU held that the authorities of a Mem- ber State cannot refuse to issue a “Schengen visa” to an applicant, unless one of the grounds for refusal, listed in the Visa Code apply. The national authori- ties have a wide discretion to ascertain this. A visa is to be refused where there is reasonable doubt as to the applicant’s intention to leave the territory of the Member States before the expiry of the visa applied for. To determine whether there is a reasonable doubt as regards that intention, the competent authorities must carry out an individual examination of the visa application which takes into account the general situation in the applicant’s country of residence and the applicant’s individual characteristics, inter alia, his family, social and eco- nomic situation, whether he may have previously stayed legally or illegally in one of the Member States and his ties in his country of residence and in the Member States.

Under Article 21 of the Convention implementing the Schengen Agreement,[22] third- country nationals who hold uniform visas and who have legally entered the territory of a Schengen state may freely move within the whole Schengen area while their visas are still valid. According to the same article, a residence permit accompanied by travel documents may under certain circumstances replace a visa. Regulation

(EC) No. 1030/2002 lays down a uniform format for residence permits.[23] Aliens not subject to a visa requirement may move freely within the Schengen territory for a maximum period of three months during the six months following the date of first entry, provided that they fulfil the entry conditions.

The Schengen Borders Code (Regulation (EC) No. 562/2006 amended by Regula- tion (EU) No. 1051/2013) abolished internal border controls, except for exceptional cases. The CJEU has held that states cannot conduct surveillance at internal borders, which has an equivalent effect to border checks.[24] Surveillance, including through electronic means, of internal Schengen borders is allowed when based on evi- dence of irregular residence, but it is subject to certain limitations, such as intensity and frequency.[25]

1.2. Preventing unauthorised entry

Under EU law, measures have been taken to prevent unauthorised access to EU ter- ritory. The Carriers Sanctions Directive (2001/51/EC) provides for sanctions against those who transport undocumented migrants into the EU.

The Facilitation Directive (2002/90/EC) defines unauthorised entry, transit and resi- dence and provides for sanctions against those who facilitate such breaches. Such sanctions must be effective, proportionate and dissuasive (Article 3). EU Member States can decide not to sanction humanitarian assistance, but they are not obliged to do so (Article 1 (2)).

1.3. Entry bans and Schengen alerts

An entry ban prohibits individuals from entering a state from which they have been expelled. The ban is typically valid for a certain period of time and ensures that indi- viduals who are considered dangerous or non-desirable are not given a visa or oth- erwise admitted to enter the territory.

Under EU law, entry bans are entered into a database called the Schengen Informa- tion System (SIS), which the authorities of other states signatory to the Schengen Agreement can access and consult. In practice, this is the only way that the issu- ing state of an entry ban can ensure that the banned third-country national will not come back to its territory by entering through another EU Member State of the Schengen area and then moving freely without border controls. The Schengen Infor- mation System was replaced by the second-generation Schengen Information Sys- tem (SIS II), which started to be operational on 9 April 2013.[26] SIS II, whose legal bases are the SIS II Regulation [27] and the SIS II Decision,[28] is a more advanced version of the system and has enhanced functionalities, such as the capability to use biom- etrics and improved possibilities for queries. Entry bans can be challenged.

Example: In the M. et Mme Forabosco case, the French Council of State (Con- seil d’État) quashed the decision denying a visa to M Forabosco’s wife who was listed on the SIS database by the German authorities on the basis that her asy- lum application in Germany had been rejected. The French Council of State held that the entry ban on the SIS database resulting from a negative asylum deci- sion was an insufficient reason for refusing a French long-term visa.[29]

Example: In the M. Hicham B case, the French Council of State ordered a tempo- rary suspension of a decision to expel an alien because he had been listed on the SIS database. The decision to expel the alien mentioned the SIS listing but without indicating from which country the SIS listing originated. Since expulsion decisions must contain reasons of law and fact, the expulsion order was consid- ered to be illegal.[30]

For those individuals subject to an entry ban made in the context of a return order under the Return Directive (Directive 2008/115/EC),[31] the ban should normally not extend beyond five years.[32] It will normally be accompanied by an SIS alert and they will be denied access to the whole Schengen area. The EU Member State which has issued an entry ban will have to withdraw it before any other EU Member State can grant a visa or admit the person. Since the ban may have been predicated on a situ- ation which was specific to the state that issued it, questions arise as to the propor- tionality of a Schengen-wide ban, particularly in situations involving other funda- mental rights, such as when reuniting a family.

Entry bans issued outside the scope of the Return Directive do not formally bar other states from allowing access to the Schengen area. Other states, however, may take entry bans into account when deciding whether to issue a visa or allow admission. The bans may therefore have effects across the Schengen area, even though a ban may only be relevant to the issuing state that deems an individual undesirable, including, for example, for reasons related to disturbing political stability: a Schengen alert issued on a Russian politician by an EU Member State prevented a member of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) from attending ses- sions of the parliament in France. This was discussed in detail at the October 2011 meeting of the PACE Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights, which led to the preparation of a report on restrictions of freedom of movement as punishment for political positions.[33]

Under the ECHR, placing someone on the SIS database is an action taken by an indi- vidual Member State within the scope of EU law. As such, complaints can be brought to the ECtHR alleging that the state in question violated the ECHR in placing or retain- ing someone on the list.

Example: In the Dalea v. France case, a Romanian citizen whose name had been listed on the SIS database by France before Romania joined the EU was unable to conduct his business or provide or receive services in any of the Schengen area states. His complaint that this was an interference with his right to conduct his professional activities (protected under Article 8 of the ECHR on the right to respect for private and family life) was declared inadmissible. In its first Cham- ber decision concerning registration on the SIS database and its effects, the Court considered that the state’s margin of appreciation in determining how to provide safeguards against arbitrariness is wider as regards entry into national territory than in relation to expulsion.[34]

The ECtHR has also had to consider the effects of a travel ban imposed as a result of placing an individual on an UN-administered list of terrorist suspects as well as designed to prevent breaches of domestic or foreign immigration laws.

Example: The Nada v. Switzerland case[35] concerned an Italian-Egyptian national, living in Campione d’Italia (an Italian enclave in Switzerland), who was placed on the ‘Federal Taliban Ordinance’ by the Swiss authorities which had imple- mented UN Security Council anti-terrorism sanctions. The listing prevented the applicant from leaving Campione d’Italia, and his attempts to have his name removed from that list were refused. The ECtHR noted that the Swiss authorities had enjoyed a certain degree of discretion in the application of the UN counter- terrorism resolutions. The Court went on to find that Switzerland had violated the applicant’s rights under Article 8 of the ECHR by failing to alert Italy or the UN-created Sanctions Committee promptly that there was no reasonable suspi- cion against the applicant and to adapt the effects of the sanctions regime to his individual situation. It also found that Switzerland had violated Article 13 of the ECHR in conjunction with Article 8 as the applicant did not have any effective means of obtaining the removal of his name from the list.

Example: The Stamose v. Bulgaria[36] case concerned a Bulgarian national upon whom the Bulgarian authorities imposed a two years travel ban on account of breaches of the U.S. immigration laws. Assessing for the first time whether a travel ban designed to prevent breaches of domestic or foreign immigration laws was compatible with Article 2 Protocol No. 4 ECHR, the ECtHR found that a blanket and indiscriminate measure prohibiting the applicant from travelling to every foreign country due to the breach of the immigration law of one particu- lar country was not proportionate.

1.4. Border checks

Article 6 of the Schengen Borders Code requires that border control tasks have to be carried out in full respect of human dignity.[37] Controls have to be carried out in a way which does not discriminate against a person on grounds of sex, racial or ethnic origin, religion or belief, disability, age or sexual orientation. More favourable rules exist for third-country nationals who enjoy free movement rights (Articles 3 and 7 (6)). A mechanism has been set up to evaluate and monitor the application of the Schengen acquis (Regulation (EU) No. 1053/2013).

Under the ECHR, the requirement for a Muslim woman to remove her headscarf for an identity check at a consulate or for a Sikh man to remove his turban at an air- port security check was found not to violate their right to freedom of religion under Article 9 of the ECHR.[38]

In the case of Ranjit Singh v. France, the UN Human Rights Committee considered that the obligation for a Sikh man to remove his turban in order to have his offi- cial identity photo taken amounted to a violation of Article 18 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), not accepting the argument that the requirement to appear bareheaded on an identity photo was necessary to protect public safety and order. The reasoning of the UN Human Rights Committee was that the state had not explained why the wearing of a Sikh turban would make it more difficult to identify a person, who wears that turban all the time, or how this would increase the possibility of fraud or falsification of documents. The com- mittee also took into account the fact that an identity photo without the turban might result in the person concerned being compelled to remove his turban during identity checks.[39]

1.5. Transit zones

States have sometimes tried to argue that individuals in transit zones do not fall within their jurisdiction.

Under EU law, Article 4 (4) of the Return Directive sets out minimum rights that are also to be applied to persons apprehended or intercepted in connection with their irregular border crossing.

Under the ECHR, the state’s responsibility may be engaged in the case of persons staying in a transit zone.

Example: In Amuur v. France,[40] the applicants were held in the transit zone of a Paris airport. The French authorities argued that as the applicants had not ‘entered’ France, they did not fall within French jurisdiction. The ECtHR disa- greed and concluded that the domestic law provisions in force at the time did not sufficiently guarantee the applicants’ right to liberty under Article 5 (1) of the ECHR.[41]

1.6. Asylum seekers

Under EU law, the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights provides for the right to asy- lum in Article 18 and the prohibition of refoulement in Article 19. Article 78 of the TFEU provides for the creation of a Common European Asylum System which must respect states’ obligations under the 1951 Geneva Convention. Several legislative instruments have been adopted to implement this provision. They also reflect the protection from refoulement contained in Article 33 of the 1951 Geneva Convention.

Although Article 18 of the Charter guarantees the right to asylum, EU law does not provide for ways to facilitate the arrival of asylum seekers. Individuals who wish to seek asylum in the EU are primarily nationals of countries requiring a visa to enter the EU. As these individuals often do not qualify for an ordinary visa, they may have to cross the border in an irregular manner.

Article 3 (1) of the Dublin Regulation (Regulation (EU) No. 604/2013) requires that EU Member States examine any application for international protection lodged by a third-country national or a stateless person and that such application be examined by one single Member State. The EU asylum acquis only applies from the moment an individual has arrived at the border, including territorial waters and transit zones (Article 3 (1) of the Asylum Procedures Directive (2013/32/EU)). For those claims, Article 6 of the directive lays down details on access to the asylum procedure. In particular, Article 6 (1) requires states to register an application within three work- ing days or, within six working days, when an application is submitted to authori- ties other than those responsible for its registration. Article 6 (2) obliges states to ensure that individuals have an effective opprortunity to lodge an application as soon as possible. The safeguards in the directive are triggered by accessing the pro- cedures. They do not apply to those who cannot reach the territory, the border or a transit zone.

Article 43 of the Asylum Procedures Directive permits the processing of asylum applications at the border. There, decisions can be taken on the inadmissibility of the application. Decisions can also be taken on its substance in circumstances in which accelerated procedures may be used in accordance with Article 31 (8) of the directive. The basic principles and guarantees applicable to asylum claims submitted inside the territory apply. Article 43 (2) stipulates that in border proce- dures a decision must be taken at the latest within four weeks from the submis- sion of the claim; otherwise the applicant must be granted access to the territory. There is a duty under Article 24 (3) to refrain from using border procedures for applicants in need of special procedural guarantees who are survivors of rape or other serious violence, where adequate support cannot be provided at the border. Article 25 (6) (b) sets some limitations to the processing of applications submitted at the border by unaccompanied minors. These provisions do not apply to Ireland and the United Kingdom, which remain bound by Article 35 of the 2005 version of the Directive (2005/85/EC).

Under the ECHR, there is no right to asylum as such. Turning away an individual, however, whether at the border or elsewhere within a state’s jurisdiction, thereby putting the individual at risk of torture or inhuman or degrading treatment or punish- ment, is prohibited by Article 3 of the ECHR. In extreme cases, a removal, extradition or expulsion may also raise an issue under Article 2 of the ECHR which protects the right to life.

The former European Commission of Human Rights examined a number of cases of ‘refugees in orbit’ where no country would accept responsibility for allowing them to enter its territory in order for their claims to be processed.

Example: The East African Asians case[42] concerned the situation of British pass- port holders with no right to reside in or enter the United Kingdom and who had been expelled from British dependencies in Africa. This left them ‘in orbit’. The former European Commission of Human Rights concluded that, apart from any consideration of Article 14 of the ECHR, discrimination based on race could in certain circumstances of itself amount to degrading treatment within the mean- ing of Article 3 of the ECHR.

1.7. Push backs at sea

Access to EU territory and Council of Europe member states may be by air, land or sea. Border surveillance operations carried out at sea not only need to respect human rights and refugee law, but must also be in line with the international law of the sea.

Activities on the high seas are regulated by the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea as well as by the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) and Search and Rescue (SAR) Conventions. These instruments contain a duty to render assistance and rescue per- sons in distress at sea. A ship’s captain is furthermore under the obligation to deliver those rescued at sea to a ‘place of safety’.

In this context, one of the most controversial issues is where to disembark persons rescued or intercepted at sea.

Under EU law, Article 12, read in conjunction with Articles 3 and 3a[43] of the Schen- gen Borders Code, stipulates that border management activities must respect the principle of non-refoulement. Given the complexity of the issue, the EU adopted guidelines to assist Frontex in the implementation of operations at sea.[44] The CJEU annulled the guidelines and the European Commission presented a proposal for a new regulation.45

Example: In European Parliament v. Council of the EU,[46] the European Parliament called on the CJEU to pronounce itself on the legality of the guidelines for Frontex operations at sea (Council Decision 2010/252/EU). The guidelines were adopted under the comitology procedure regulated in Article 5 a of Decision 1999/468/EC without full involvement of the European Parliament. The CJEU annulled them, despite stating that they should continue to remain in force until replaced. The CJEU pointed out that the adopted rules contained essential elements of exter- nal maritime border surveillance and thus entailed political choices, which must be made following the ordinary legislative procedure with the Parliament as co-legislator. Moreover, the Court noticed that the new measures contained in the contested decision were likely to affect individuals’ personal freedoms and fun- damental rights and therefore these measures again required the ordinary proce- dure to be followed. According to the Court, the fact that the provisions contained in Part II (‘Guidelines for search and rescue situations and or disembarkation in the context of sea border operations coordinated by the Agency’) to the Annex to Council Decision 2010/252/EC were referred to as guidelines and were said to be non-binding by Article 1 did not affect their classification as essential rules.

Under the ECHR, the Convention applies to all those who are ‘within the jurisdic- tion’ of a Council of Europe member state. The ECtHR has held on several occasions[47] that individuals may fall within its jurisdiction when a state exercises control over them on the high seas. In a 2012 case against Italy, the ECtHR’s Grand Chamber set out the rights of migrants seeking to reach European soil and the duties of states in such circumstances.

Example: In Hirsi Jamaa and Others v. Italy,[48] the applicants were part of a group of about 200 migrants, including asylum seekers and others, who had been intercepted by the Italian coastguards on the high seas while within Malta’s search and rescue area. The migrants were summarily returned to Libya under an agreement concluded between Italy and Libya, and were given no opportu- nity to apply for asylum. No record was taken of their names or nationalities. The ECtHR noted that the situation in Libya was well-known and easy to verify on the basis of multiple sources. It therefore considered that the Italian authori- ties knew, or should have known, that the applicants, when returned to Libya

as irregular migrants, would be exposed to treatment in breach of the ECHR and that they would not be given any kind of protection. They also knew, or should have known, that there were insufficient guarantees protecting the applicants from the risk of being arbitrarily returned to their countries of origin, which included Somalia and Eritrea. The Italian authorities should have had particular regard to the lack of any asylum procedure and the impossibility of making the Libyan authorities recognise the refugee status granted by UNHCR.

The ECtHR reaffirmed that the fact that the applicants had failed to ask for asylum or to describe the risks they faced as a result of the lack of an asylum system in Libya did not exempt Italy from complying with its obligations under Article 3 of the ECHR. It reiterated that the Italian authorities should have ascer- tained how the Libyan authorities fulfilled their international obligations in rela- tion to the protection of refugees. The transfer of the applicants to Libya there- fore violated Article 3 of the ECHR because it exposed the applicants to the risk of refoulement.

1.8. Remedies

As regards remedies, Chapter 4 on procedural safeguards will look at this issue in more depth, while Chapter 6 will address remedies in the context of deprivation of liberty.

Under EU law, some instruments – such as the Visa Code (Articles 32 (3) and 34 (7)), the Schengen Borders Code (Article 13) and the Asylum Procedures Direc- tive (Article 46) – make provision for specific appeals and remedies. Article 47 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights also provides for a more general guaran- tee. All individuals who allege to having been the victim of a violation of the rights and freedoms guaranteed by EU law, including violation of a Charter provision, must automatically have access to an effective remedy which includes ‘effec- tive judicial protection’ against a refusal of access to the territory or access to the procedures involved.

Under the ECHR, all those whose access to the territory or to procedures arguably engages rights guaranteed under the ECHR must, under Article 13 of the ECHR, have access to an effective remedy before a national authority. For example, in the Hirsi Jamaa and Others v. Italy case, the ECtHR found that there was no such remedy because the migrants had been sent back to Libya without having been afforded the possibility to challenge this measure.

Key points

- States have a right to decide whether to grant foreigners access to their territory, but must respect EU law, the ECHR and applicable human rights guarantees (see Intro- duction to this chapter).

- EU law establishes common rules for EU Member States regarding the issuance of short-term visas (see Section 1.1).

- EU law contains safeguards relating to the implementation of border control (see Section 1.4) and border surveillance activities, particularly at sea (see Section 1.7).

- EU law, particularly the Schengen acquis, enables individuals to travel free from bor- der controls within the agreed area (see Section 1.1).

- Under EU law, an entry ban against an individual by a single state of the Schengen area can deny that individual access to the entire Schengen area (see Section 1.3).

- The EU Charter of Fundamental Rights provides for the right to asylum and for the prohibition of refoulement. The EU asylum acquis applies from the moment an indi- vidual has arrived at an EU border (see Section 1.6).

- In certain circumstances, the ECHR imposes limitations on the right of a state to detain or turn away a migrant at its border (see Introduction to this chapter and Sections 1.5 and 1.6), regardless of whether the migrant is in a transit zone or other- wise within that state’s jurisdiction. The state may also be required to provide a rem- edy whereby the alleged violation of the ECHR can be put before a national authority (see Sections 1.7 and 1.8).

Further case law and reading:

To access further case law, please consult the guidelines on page 249 of this hand- book. Additional materials relating to the issues covered in this chapter can be found in the Further reading section page 227.

______________

16. Regulation (EC) No. 2007/2004, 26 October 2004, OJ 2004 L 349/1; Regulation (EU) No. 1168/2011, 25 October 2011, OJ 2011 L 304/1.

17. Regulation (EC) No. 863/2007, 11 July 2007, OJ 2007 L 199/30.

18. For more information, see ECtHR, Abdulaziz, Cabales and Balkandali v. the United Kingdom, Nos. 9214/80, 9473/81 and 9474/81, 28 May 1985, paras. 82-83.

19. European Commission, Home Affairs, Visa Policies, available at: http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/borders-and-visas/schengen/index_en.htm.

20. Additional Protocol to the Ankara Agreement, OJ 1972 L 293, Art. 41.

21. CJEU, Case C-84/12, Rahmanian Koushkaki v. Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 19 December 2013.

22. Convention implementing the Schengen Agreement of 14 June 1985 between the Governments of the States of the Benelux Economic Union, the Federal Republic of Germany and the French Republic on the gradual abolition of checks at their common borders, OJ 2000 L 249/19.

23. Council Regulation (EC) No. 1030/2002, laying down a uniform format for residence permits for thirdcountry nationals, 13 June 2002, OJ 2002 L 157, as amended by Regulation (EC) No. 380/2008/EC, OJ 2008 L 115/1.

24. CJEU, Joined Cases C-188/10 and C-189/10, [2010] ECR I-05667, Aziz Melki and Selim Abdeli [GC], para. 74.

25. CJEU, Case C-278/12 PPU, Atiqullah Adil v. Minister voor Immigratie, Integratie en Asiel, 19 July 2012.

26. For matters falling within the scope of Title IV of the Treaty establishing the European Community see: Council Decision 2013/158/EU of 7 March 2013 fixing the date of application of Regulation (EC) No. 1987/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the establishment, operation and use of the second generation Schengen Information System (SIS II), OJ 2013 L87, p. 10; for matters falling within the scope of Title VI of the Treaty on European Union see: Council Decision 2013/157/EU

of 7 March fixing the date of application of Decision 2007/533/JHA on the establishment, operation and use of the second generation Schengen Information System (SIS II), OJ 2013 L87, p. 8.

27. Regulation (EC) No. 1987/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council, 20 December 2006, OJ 2006 L 381/4.

28. Council Decision 2007/533/JHA, 12 June 2007, OJ 2007 L 205/63.

29. France, Council of State (Conseil d’État), M. et Mme Forabosco, No. 190384, 9 June 1999.

30. France, Council of State (Conseil d’État), M. Hicham B, No. 344411, 24 November 2010.

31. Directive 2008/115/EC, OJ 2008 L 348, Art. 3 (6) and Art. 1.

32. CJEU, Case C-297/12, Criminal proceedings against Gjoko Filev and Adnan Osmani, 19 September 2013.

33. Council of Europe, Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights (2012), The inadmissibility of restrictions on freedom of movement as punishment for political positions, 1 June 2012 and Resolution No. 1894 (provisional version), adopted on 29 June 2012.

34. ECtHR, Dalea v. France (dec.) No. 964/07, 2 February 2010.

35. ECtHR, Nada v. Switzerland [GC], No. 10593/08, 12 September 2012.

36. ECtHR, Stamose v. Bulgaria, No. 29713/05, 27 November 2012.

37. See CJEU, Case C23/12, Mohamad Zakaria, 17 January 2013.

38. ECtHR, Phull v. France (dec.), No. 35753/03, 11 January 2005; ECtHR, El Morsli v. France (dec.), No. 15585/06, 4 March 2008.

39. UN Human Rights Committee, Ranjit Singh v. France, Communications Nos. 1876/2000 and 1876/2009, views of 22 July 2011, para. 8.4.

40. ECtHR, Amuur v. France, No. 19776/92, 25 June 1996, paras. 52-54.

41. See also ECtHR, Nolan and K v. Russia, No. 2512/04, 12 February 2009; ECtHR, Riad and Idiab v. Belgium, Nos. 29787/03 and 29810/03, 24 January 2008.

42. European Commission of Human Rights, East African Asians (British protected persons) v. the United Kingdom (dec.), Nos. 4715/70, 4783/71 and 4827/71, 6 March 1978.

43. Article 3a has been introduced by Regulation (EU) No. 610/2013 of 26 June 2013 amending the Schengen Borders Code, OJ 2013 L 182/1.

44. Council Decision 2010/252/EU, 26 April 2010, OJ 2010 L 111/20.

45. European Commission, COM(2013) 197 final, Brussels, 12 April 2013.

46. CJEU, Case C-355/10 [2012], European Parliament v. Council of the EU, 5 September 2012, paras. 63-85.

47. ECtHR, Xhavara and Others v. Italy and Albania (dec.), No. 39473/98, 11 January 2001; ECtHR, Medvedyev and Others v. France [GC], No. 3394/03, 29 March, 2010.

48. ECtHR, Hirsi Jamaa and Others v. Italy [GC], No. 27765/09, 23 February 2012.

Leave a Reply